One of the most harmful implications we make in the Church is that a service or sanctuary is where you go to experience God’s presence—as if His presence is not ablaze all around us, all the time.

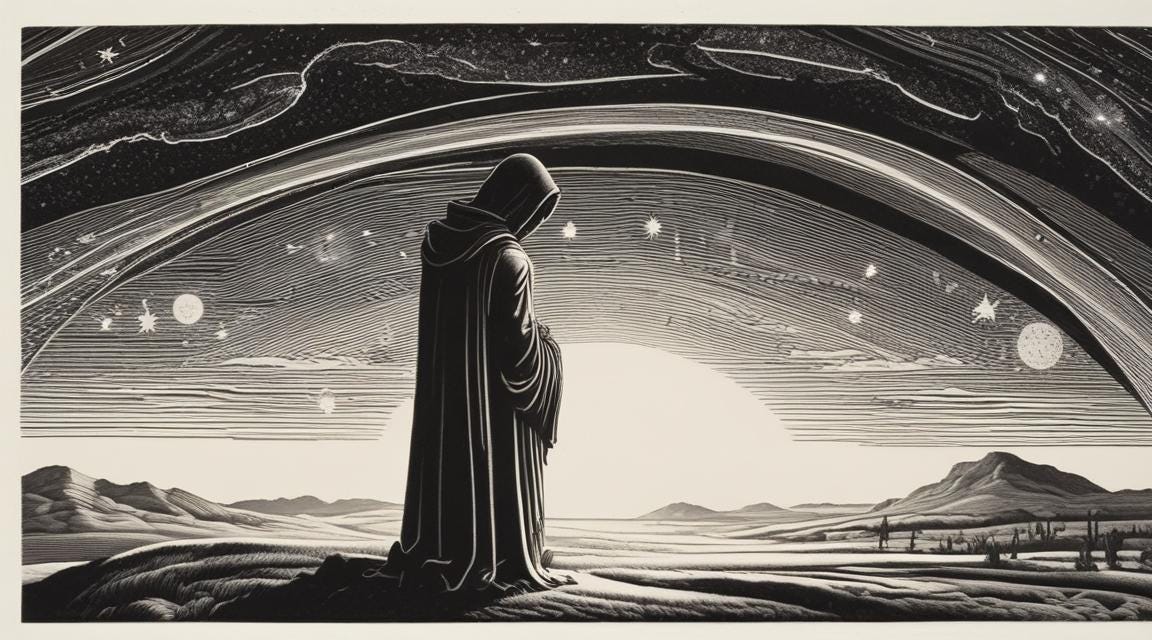

In 1923, somewhere in the sands of the Ordos Desert near the border between China and Mongolia, a Jesuit priest and paleontologist one day found himself yearning for God, but far away from any church.

When not on expedition, and per his tradition, he would normally make his way to Mass each day to partake in the Eucharist. But here, in the remote obscurity of the Asian steppe, there was no bread, there was no wine. Instead, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin unexpectedly took a different kind of communion, and fell into an ecstatic awareness of God’s presence.

He saw the Divine bursting within all matter and every molecule. He saw Christ animating every living thing. He realized the presence of God inhabiting all energy, space, and change.

He captured what his soul saw in an essay, “Mass on the World,” where he wrote:

“Radiant Word, blazing Power, you who mould the manifold so as to breathe your life into it; I pray you, lay on us those your hands — powerful, considerate, omnipresent, those hands which do not (like our human hands) touch now here, now there, but which plunge into the depths and the totality, present and past, of things so as to reach us simultaneously through all that is most immense and most inward within us and around us.”

Teilhard spent the rest of his life in the afterglow of such a vision, contemplating the presence of God that had become so much more real to him in the desert than in any cathedral.

His experience that day joined him with the long, rich heritage of men who had encountered God in similar settings—deserts far removed from the shelters of formal religion. Abraham, Moses, Jacob, Elijah, even Jesus.

In fact we find far more instances in scripture of people encountering God in wild, lonely places than in structured religious gatherings. If God has a favorite place to find us, then surely it is not inside of churches.

This is why one of the most harmful implications we make in the Church is that a service or sanctuary is where you go to experience God’s presence—as if His presence is not ablaze all around us, all the time.

We know, of course, that God is omnipresent. But we so often speak and act as if church gatherings grant special access to Him.

Sunday services become the epicenter of “being in” God’s presence and receiving God’s word. Preachers become mediators for God’s voice. The measure of Christian piety begins with the frequency of our attendance at church. It’s the old temple system reborn, just wearing different clothes.

When we train people to see one hour on Sunday morning as the place of God’s presence, we condition them to miss it everywhere else. How many faithful pilgrims walked right past the Messiah, unaware, on their way to the temple where they would pray for His coming?

When Christ gave up His spirit on the cross, graves rumbled open, the earth shook, and the temple veil tore in two. It was a jailbreak of the Divine—Presence released from its confines and into the wild. So it is ironic that the word we use to separate what is sacred from what is not, “profane,” comes from the Latin root word which means “outside the temple.”

What made Jesus’ ministry and message so scandalous to the pious and so revolutionary to everyone else was that it was outside the temple. It escaped the structures of the religious system, and it escaped the expectations of those who thought they knew what the Messiah’s coming would be like.

But we have become so fixated on attendance in church that we have neglected to cultivate awareness. Awareness of the presence of God in all things, in all places. Maybe our message should be changing from “come to church” to “open your eyes.”

In Genesis 28, Jacob, alone in the middle of nowhere, awoke from dreams of angels and cried “Surely the Lord is in this place, and I was not aware of it.” He then anointed the stone that had been his pillow, and named that place Bethel—”the house of God.”

The radical lesson of that moment is that Jacob did not seek out a “house of God” to hear God’s voice. Rather, he recognized that in that wild place he was already in the house of God. It was not a “going-to,” it was a waking up.

The presence of God is not something that we visit—it is always visiting us. But we are usually missing it. It is something we must wake up to. And the kind of spiritual development we desperately need is not one that revolves around our attendance in one place, but one that helps us realize God’s presence in every place. In the kitchen after an argument. In the anxiety of the hospital waiting room. In the middle seat on the airplane. At 2:37AM when the baby is still screaming. In the setting sun. On the way to where we’re going, and when we get there.

Of course there is immense value in the gathering of the church. For edification, for learning, for corporate praise and prayer. And, critically, for developing the skill of recognizing God’s presence. But it is not the home of God’s presence.

Church attendance is not the main event of our faith. That’s temple religion. And when the gathering becomes an end in itself rather than a place of preparation and training for the wilderness, it fails us. Perhaps the reason that church attendance continues to plummet is because we have tried so hard to make it a focal point of our faith that it was never meant to be. Perhaps people are losing their taste for the temple.

Maybe the way we “do” church needs a waking up of its own. Instead of church services that promise a presence they do not have dominion over, I see gatherings like reunions of joyful travelers trading stories of where they met God that week—lakesides, weddings, gardens, city streets, dinner parties, mountaintops, and all the other kinds of places that Jesus walked. Stopping in to celebrate and share for a while on their way to and from wherever they might discover God next.

When we live our lives as if God only meets us in church services or quiet times, and not also in nature, art, people, celebration, suffering, and all the mundane in between, we stitch back up the veil that was torn when Jesus died and close the temple doors. Every time we confine God to a particular place or area of our lives, we must shrink Him. Eventually, we end up with a tiny God who inhabits only certain cracks and crevices of the world, much like the mythical elves and fairies that the pagans believed in.

May we, like Teilhard did, realize that God is immeasurably more real and present than we ever dared to imagine. May we, like Jacob did, wake up and realize that the Lord is in this place.

Wow, this is Good. For me, I experience the presence of God, both inside and outside the sanctuary. As a Catholic, daily and weekly mass is a high point centered on the Eucharist, or in Eucharistic Adoration, which typically occur in the church, but at the same time, I went hiking in the Colorado Rockies this week and prayed and wept and laughed with God's joy over all that I encountered physically and spiritually on the hike!

This is phenomenal - shared with family and friends!