There are few things more fundamental or more restorative than looking up and feeling small. It seems no coincidence that as our vision of creation has caved in, we have become larger in our own eyes. We are swollen selves at the center of a sad, shrinking universe. And we are miserable for it.

Anxiety

A few months ago, I was finally diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

The diagnosis came after a nearly yearlong odyssey of testing, symptom-searching and doctors visits. EKG’s, blood draws, a heart monitor, and a stint in the ER. The symptoms came in waves—breathlessness, chest pain, worrying heart palpitations—sometimes only mildly distracting, other times paralyzing and debilitating. I’d lost count of how many nights I’d spent, begging God through tearful prayers to pry away the panic that gripped my chest. To let me sleep.

Drugs were prescribed, counseling was recommended. There are more good days now, and still some bad ones too. It all still feels strange—better, but not quite solved. As I’ve observed myself this past year, scouring for any pattern that could point me to relief, I’ve noticed only one: the more I think about how I feel, the worse I feel.

It’s a maddening formula. When something feels off in your body, you are programmed to think about it. To look for danger, to identify the source of the issue, and to fix it. And trying not to think about it only seems to guarantee that you will.

But occasionally I realize that hours have passed without a single symptom, normally when I’ve been engrossed in writing, walking in nature, playing with my daughters, or in an interesting conversation with a friend. When, in other words, I have forgotten myself. This too is maddening. How could it be that every effort to get to the bottom of my condition, to get better, only seems to make things worse? How could it be that the thing that soothes me the most is to think about anything other than me?

As much pain and worry as this season has brought me, I am grateful for it in a way. Because it has led me on an exploration of a simple but seismic truth about my nature and yours:

Our misery is directly connected to our self-consciousness.

“Me is a disease.”

-Naval Ravikant

Mirrors

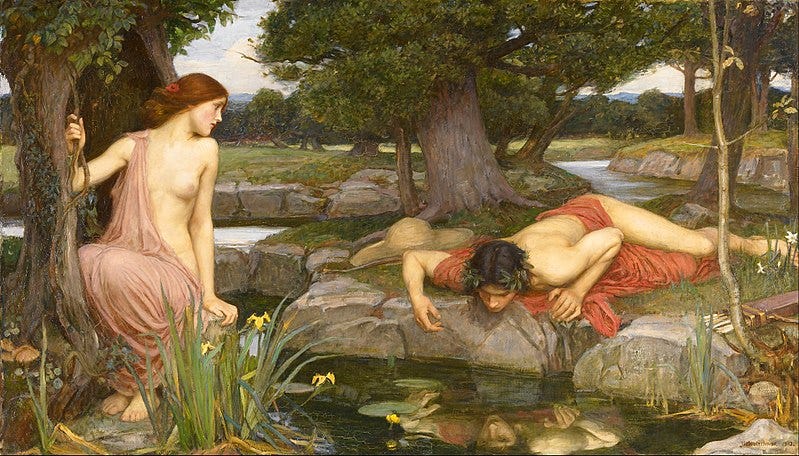

Around the time that Jesus was a child in Judea, astounding rabbis in the temple with his wisdom, the Roman poet Ovid released his magnum opus, the “Metamorphoses.” Among its many stories was the myth of Narcissus, a tragic warning about self-obsession.

Narcissus, the son of a river god and a nymph, was famous for his extraordinary beauty. One day he knelt to drink from a pool of water and was captivated by his own reflection. He was infatuated, entranced, obsessed. He could not look away and began to despair, and eventually died of thirst at the edge of the water.

To the people of antiquity, Narcissus was an extreme example of the deadly consequences of self-love, but he could be the emblem of the norm today. Modern history has been a sharply bending arc toward individualism and self-absorption.

First, there came the mirror.

In the 16th century, thanks to the ingenuity of a group of Venetian craftsmen, the glass mirror was introduced to the world. Generations of humans had only seen crude glimpses of their own faces—in pools of water, or in polished metals. Now the ability to see oneself clearly was available for purchase.

The advent of the mirror ushered in a new sense of self-awareness and individual dignity. No longer were people only known by how others saw them or by what group they belonged to. Now they could look into their own eyes, and contemplate their own quality.

It seems no coincidence that this simple innovation unfolded during the heyday of the Renaissance—the movement that popularized humanist ideals across Europe, declaring the ancient words of Protagoras: “man is the measure of all things.” But with this new sense of self-knowing came the seeds of self-consciousness, self-obsession and self-loathing.

Since that age, mankind has only marched more deeply down the footsteps of Narcissus. The Renaissance gave way to the Enlightenment, which birthed secularism, which has yielded rampant hyper-individualism in the West. And along the way our mirrors have only gotten better, brighter and more ubiquitous, and now they go by many names—selfies, Zoom calls, profile pictures. No generation of human beings has ever been as conscious of and consumed with themselves as we are. And it seems were are starting to pay the price.

The past few decades have seen an uncontrollable growth of mental illness in our nation, fueled by obsessive, self-fixated thought patterns. We are more depressed, more anxious, more distracted than any of our ancestors.

As mental health diagnoses have ballooned, so has our treatment of them. “In the US, since 1986, nearly every decade has seen a doubling of expenditure on mental health over the one before” (Abigail Shrier). The number of psychologists, counselors and therapists has skyrocketed in our lifetime, with no signs of slowing. But the mental health crisis is showing no signs of slowing, either. Our exponential efforts to treat anxiety and depression are, at least at the population level, definitively not working. Something is wrong. What have we missed?

A 2022 study led by Johan Ormel, professor of psychiatric epidemiology from The University of Groningen, investigated this mystery. How could it be that massive increases in mental health resources have resulted in virtually no decrease in mental illness in any Western nation? Ormel and his team introduced the “Treatment-Prevalence Paradox”—the vexing phenomenon that the more we treatment we give, the more sickness we have. Not only is our treatment not making things better, it appears to be making things worse.

At least in part, it seems that the cure itself is making us sicker. Rumination—compulsive preoccupation with one’s own thoughts—is both a hallmark symptom and cause of depression. Yet many applications of psychotherapy seem to inflame the rumination that put us in therapy in the first place.

If an imbalanced fixation on oneself is at the heart of so many of these disorders, then magnifying and scrutinizing one’s own thought life might be the worst kind of remedy. Like treating a burn victim with fire, the medicine is just more of the poison. There is value in investigating and appraising one’s own thoughts, but past a certain point, well-intended therapy becomes a dark mirror of its own; the returns diminish and the side effects skyrocket.

In spite of all our good intentions and billions of dollars invested in mental health, we may have missed a fundamental human truth that seems almost too obvious. The combined findings of studies like Ormel’s, ancient wisdom, and our own gut intuition all resound: fixating on ourselves is deadly.

“There was a door. And I could not open it. I could not touch the handle. Why could I not walk out of my prison? What is hell? Hell is oneself.

Hell is alone, the other figures in it

Merely projections. There is nothing to escape from

And nothing to escape to. One is always alone.”― T.S. Eliot (from ‘The Cocktail Party’)

Awe

Modern psychology long held that there are five fundamental emotions: anger, fear, disgust, happiness, and sadness. In his landmark paper in 2003, psychologist Dacher Keltner introduced a sixth: Awe.

Awe had traditionally been regarded as the domain of religion—a real, but abstract, experience, not qualified for serious study. Keltner’s work changed that entirely. He found that awe is a measurably different emotion from the other five, with measurable physical and psychological effects.

When we experience awe—witnessing the wonder of childbirth, contemplating the stars on a clear night, or during a mystical spiritual experience—our bodies respond in profound ways. Our breathing and heart rate slow down. Our jaw relaxes and our eyes widen. We produce increased levels of oxytocin, the “love hormone” that fosters feelings of bonding, trust and safety. We produce lower levels of cytokines, the small proteins that trigger inflammation in the body.

Most fascinating of all, awe experiences deactivate our “default mode network”—the system in our brains that is associated with self-perception. In other words, when we behold things greater and vaster than ourselves, our self-obsession fades away. The volume turns down on the self-conscious chatter that fills our minds. All our worrying about how we look, how we’re doing and what other people think of us goes away. We forget ourselves in the presence of the big mysteries of the world. And that is a healing experience.

Keltner coined this particular effect of awe “the vanishing self.” We have always known it on a primal level. It’s why we are filled with a strange reverence when we witness the sequoias, the Rockies, or a brilliant sunset over the sea. It’s why worship seems to change the atmosphere of our hearts and minds. It’s why pondering the legacy of our ancestors or the destiny of our children makes us feel connected, responsible, a part of something greater than ourselves. Awe and wonder join us to a bigger story and cure us, for a while, from the sickness of ourselves.

Maybe we’ve gotten our strategy for dealing with our despair exactly wrong. Maybe instead of magnifying our wounds, our regrets, and our traumas, what will really save us is a therapy that makes us small—one that magnifies the majesty and mystery of the world around us.

Oliver Burkeman has put forth such a notion, an approach he has termed “Cosmic Insignificance Therapy.” In summary, it’s the idea that contemplating the ineffable vastness of the cosmos, and the smallness of the self within it, can be a strangely cleansing experience. Rather than making one feel worthless, as you might expect, it actually frees us of our trivial preoccupations that make us miserable. It throws open the gates of universe, puts our problems in perspective, and invites us into a thrilling, liberating world of possibility. We just feel better when we realize we’re not the center.

This same idea that we know in our bones was a through line in the teachings of Jesus and the writings of his disciples. Pride, they warned, is the deadliest of sins. And self-obsession, self-loathing, and self-consciousness are all pride in disguise—they all make the self the center. But there is great freedom in becoming less.

The New Testament is littered with admonitions to humble ourselves. Jesus modeled the way—“he made himself nothing,” and he “did not come to be served, but to serve.” John wrote in his gospel: “He must increase, I must decrease.”

We are dared by God into a self-emptying life. A life that takes us beyond the boundaries of our little selves. Not just because it is good, but because it is good for us.

“How much happier you would be, how much more of you there would be, if the hammer of a higher God could smash your small cosmos, scattering the stars like spangles, and leave you in the open, free like other men to look up as well as down!”

- GK Chesterton

Stars

For most of mankind’s time on earth, the sky provided a nightly reminder of our smallness. Broad fields of bright stars. The Milky Way swirling with haunting purples and blues. Perhaps a sudden comet. But such a sight is now only accessible from a vanishing few remote places in the US.

Light pollution emitted from billions of artificial lights across the earth has painted the sky with a dull gray “sky glow”, and it’s getting worse year by year. Researchers estimate that in the next two decades, more than half the stars we can see tonight will become invisible to our eyes. Light pollution disrupts our sleep, contributes to depression and weight gain, and wreaks damaging effects on wildlife. Most tragically, it shrinks our sense of the universe.

There are few things more fundamental or more restorative than looking up and feeling small. It seems no coincidence that as our vision of creation has caved in, we have become larger in our own eyes. We are swollen selves at the center of a sad, shrinking universe. And we are miserable for it.

On the current trajectory of light pollution, our grandchildren may be the first humans to never have the wild, wonderful rite of seeing the twinkling lights of the cosmos on a clear night. What will we lose when we lose the stars? If there is a link between the vanishing heavens and our growing self-centered malaise, our outlook is bleak.

As I was piecing together the outline of this essay a few weeks ago, my older daughter Isla suddenly gasped from across the living room (I think she gets that from her mom). She ran over to me and, breathlessly, asked “Dad! Can we buy some s’mores and get some sticks and make a campfire and SEE THE STARS?”

It was so pure, so precious. She has always loved the sky and all its marvels, and her sense of wonder has been one of God’s favorite ways to speak to me lately. Often before bed, partially out of wonder and partially to stall brushing her teeth, she’ll pull me close and whisper “Can we go see the beautiful sky?”

Of course we went outside to look for stars. The sun had just set, and there were only a couple of stars visible. She was enamored with them (and with the couple of airplanes we could spot sliding across the sky). She doesn’t have any memory of an unpolluted sky, she doesn’t know what we’ve lost. But she’s enchanted by the handful of stars that are still left. To her, they’re a precious gift, a miracle every time she remembers they’re there. When I see her staring up at the moon, finding faces in the clouds, or scanning for stars, I see her world swing open wide. And I remember the wonder that I’ve been losing.

This must be a picture of what Jesus meant when he told his followers that they must become like children. As we grow older, he knew, we grow inward. We become less open, less curious, less impressed. We slowly nudge ourselves into the center of the universe, or else shrink and maim the universe until it is small enough to center around us. There we lose the awe and wonder that welcomes in the mystery of the glory of God. In that center, we languish.

The sad irony of Narcissus’ story is that he died from thirst right next to water. But he was too consumed with himself to see his salvation right in front of his face. Are we, too, missing the medicine that is right in front of us? Are we missing the beauty that surrounds us, the beauty that could save us, because we can’t look away from ourselves?

But there is still hope. Like Isla who suddenly remembered, in the middle of playing with toys and half watching TV, that the sky is just right outside, the beauty and mystery we desperately need is always at hand. It’s always just on the other side of our decision to look away from our reflection, and look up.

“How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it.”

-GK Chesterton

This is truth, and good writing to boot. It reminds me of when I moved from flatlands to live in the Rocky Mountains, there was this huge gut recognition of “At last! A landscape large enough to put my ego in its place!”

This resonates so much with me! Sunsets, mountains, waterfalls, oceans … the way they can catch your attention away from whatever busyness you’re occupied with in a moment, they way they inspire wonder and gratitude… I never really named that feeling before. But I love the idea that it is awe and that it’s power lies in shifting our increasing-internal perspective back out to the larger picture we are a part of ❤️