In a world where hurry and hustle have become our default speed of life, the most subversive thing we can do is be still.

HURRY SICKNESS

In 1974, cardiologists Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman introduced a novel diagnosis to the medical world.

They needed a name to describe a curious set of symptoms they were finding more and more frequently in their patients: surging cortisol that fueled depression and burnout, anxiousness and irritability, unrelenting overstimulation and an inability to relax. The symptoms were being produced not by a physiological issue in the heart, but by a “harrying sense of time urgency.”

They called this condition “hurry sickness.” And they could not have been more prescient.

Since their time, the speed of society has only increased, and the hurry of our lives has only grown. The demands of our workplaces, our homes, and our own aspirations hold us in a constant state of obligation and stress. There is always more to do, and we can never do enough.

The blessings of our modern tech age have turned out to also be curses. Social media connects us and informs us—it also enrages us and addicts us, greedily grabbing for every spare moment in our days. A never-ending advent of new apps and programs promises to make us more efficient, but they end up haunting us with the omnipresence of work that we can no longer disconnect from. The conveniences of app-enabled grocery deliveries, next-day Prime shipping, and on-demand streaming services aren’t making us anymore peaceful. The margin these luxuries create just gets filled with more and more busyness.

Friedman and Rosenman’s patients were hurrying themselves sick, but they were a small sample size. Today, hurry sickness seems to be the disease we’ve all accepted as our default reality.

When someone asks “How are you?” the only proper responses we feel we can give are “Good” (which is often a polite lie), or “Busy” (which is always true). To be slow, or bored, or unrushed, are bizarre oddities; the age-old human tradition of sitting and doing nothing has nearly gone extinct. We even fill our leisure time with devices scrolling images, inputs and diversions—anything to spare us the pain of simply being still—so even when our bodies are at rest, our minds are not.

Hurry sickness has even infected our faith. Church services are increasingly optimized down to a crisp 65 minutes, the “minimum effective dose” that has become industry standard to keep an attention-deficit congregation coming back. We approach prayer and reading the Bible the same way we approach the rest of our hectic lives—hastily and with a heavy sense of obligation. They are another thing to cross off our towering to-do list, and they must be done efficiently, because we have so much else to get to. And in the end we feel just as sick as everyone else.

This is why, in a world where hurry and hustle have become our default speed of life, the most subversive thing we can do is be still.

HOLY INACTIVITY

Brother Lawrence was a lay minister in a Carmelite monastery in France in the 17th century. He was a humble man who accrued no impressive accolades in the Church while he was alive, and found more closeness with God in the simple drudgery of washing dishes for the monks in the monastery than in the Liturgy of the Hours.

He came to be deeply admired for his simple, unhurried way of communing with God. The letters of encouragement and edification he penned to his friends were compiled into what is now a classic of Christian spirituality: “The Practice of the Presence of God.”

To Brother Lawrence, there was nothing more essential than being present with God. To Brother Lawrence, it was the only essential thing. He summarized his practice simply in this way:

“I make it my priority to persevere in His holy presence, wherein I maintain a simple attention and a fond regard for God, which I may call an actual presence of God. Or, to put it another way, it is an habitual, silent, and private conversation of the soul with God.”

He described this way of being with God as “holy inactivity.” He learned, by God’s own grace, that there is an intimacy with God that we can only attain when we stop. Stop striving. Stop toiling. Stop earning. When we do nothing else but wait in His presence.

In the same letter, he confessed:

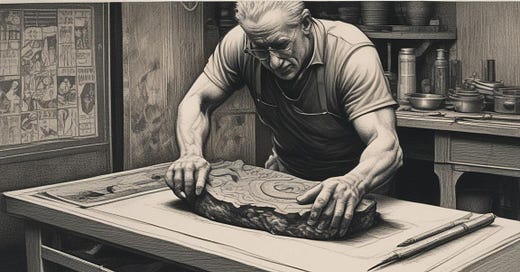

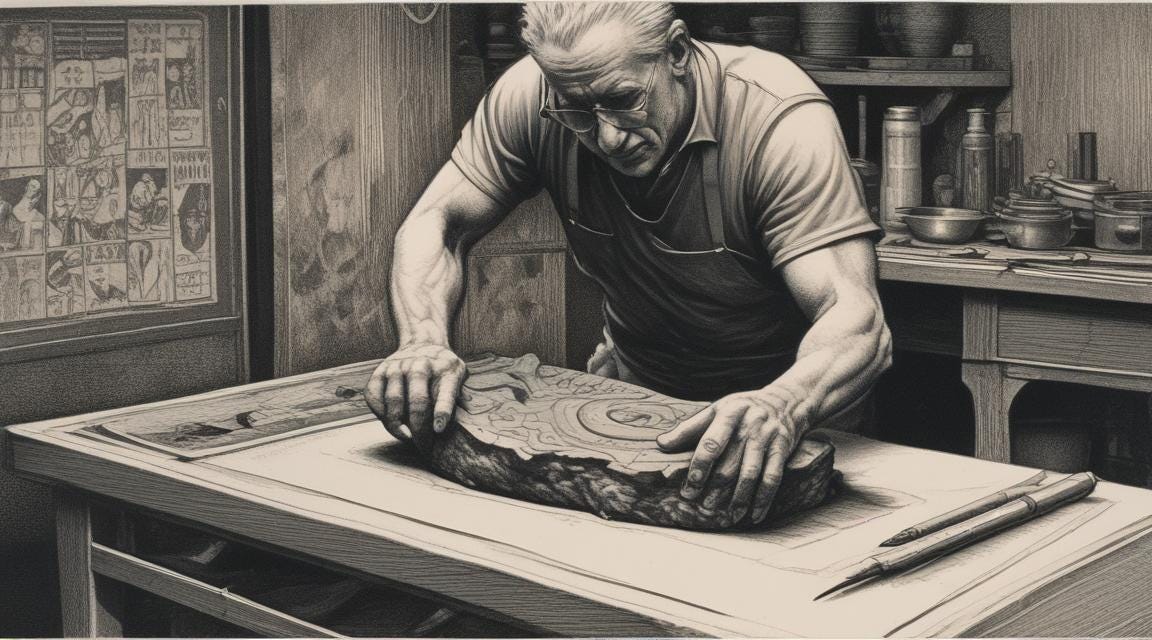

“Sometimes I consider myself as a stone before a sculptor, who is making a statue.”

God is patiently waiting to form us into who we were meant to be, down in the truest parts of who we are, past the busy, frantic surface layer of us. But we are so often squirming and wriggling out of the hands of the Sculptor.

As a generation that can barely stand to sit still for more than a few moments without reaching for a distraction, we are missing the chiseling that God wants to perform on us. We soothe our sense of Christian duty with a thin film of Christian activity, while never experiencing the deep transformation that can only come through abiding, for a while, in the presence of God.

A stone can’t be sculpted until it is still.

(Jehovah) RAPHA

“Be still and know that I am God.”

Psalm 46:10

This verse, well traveled in sermons and inspirational Christian artwork, means more than we think it does. It’s not just a simple admonishment to stop moving or stop worrying. It’s an invitation to be healed.

The Hebrew word that we’ve often translated as “be still” is rapha. Does that sound familiar?

“Jehovah Rapha” is one of the many names of God recorded in the Old Testament, meaning “The Lord who heals.”

The same root word that gives us “BE STILL” also gives us “BE HEALED.”

Beneath the iterations and translations, we can find in scripture deeper, more beautiful meaning. There is a connection between our stillness and our healing. Some injuries require a kind of surgery that we must be motionless for. A patient who cannot be still on the operating table is liable to wound themselves even worse when the surgeon is at work.

Rapha can also conjure ideas like “sink down,” “become limp,” or “loosen.” It can convey a connotation of surrender.

In our hurried way of life, we desperately want to believe we can overcome our problems with more effort, more activity. But there comes a point where our own efforts are not enough to fix what is broken in us—they can even make things worse, like an unhealed wound that is reopened by straining too soon. Our insistence on achieving through our own strength is not just making us sick, it’s eroding the most fundamental form of our faith: trusting God.

Stillness is the scariest surrender we can enter into it. It’s the place where we let go of our need for control, lay down our delusion that we can do it all, and trust that God really can take care of us. God is our healer, but we must, from time to time, be still enough to let Him work on us.

Like a stone before the great Sculptor, like a wounded patient before the great Healer, in our stillness we are made new.

The conveniences of app-enabled grocery deliveries, next-day Prime shipping, and on-demand streaming services aren’t making us anymore peaceful. The margin these luxuries create just gets filled with more and more busyness.

I do find the once a week pickup is easier for me than shopping for groceries. Hubby picks up. I don’t impulse buy. I have a list.

I’ve used it since Covid. And for me it’s peaceful. 😄

For walking I go to the park. I don’t need to be bombarded by lights, people and sounds.

“Stillness is the scariest surrender we can enter into it. It’s the place where we let go of our need for control, lay down our delusion that we can do it all, and trust that God really can take care of us. God is our healer, but we must, from time to time, be still enough to let Him work on us.”

This is beautiful and so spot on. When I get still enough and fall into presence, the answer to “How are you?” is “Enchanted.”. If there is any other answer, I know I’m not paying attention and need to slow down.