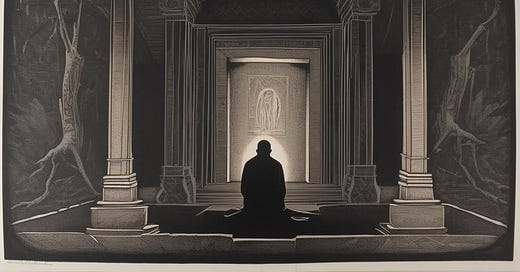

The mausoleum door slid shut and Antony, alone inside, kneeled to pray in the dark.

Soon, he heard claws clattering against the stone walls, and low growls of unseen beasts. They encircled him from the shadows. They sniffed and snarled closer and closer. He could feel the hate on their breath blowing on his face as he prayed.

Their resounding growling boiled louder into a tortured roar. Shrieking filled the tomb. Incensed that the monk was unfazed—most men would have quailed in horror by now—his hunters thrashed the walls until the tomb began to quiver and shake.

Dust and debris fell like spittle from the roof. Mortar popped like bones. The floor bowed and groaned. Still, Antony did not despair, he did not cry out. Still, Antony prayed.

More hordes slithered into the room. It was crowded now—they pressed in on him, crushing, suffocating. In their rage, they did what they usually dare not—they began to strike him. They fell like axe blows upon his body. He crumpled beneath the onslaught, but still he prayed. All through the night, they scraped and lashed at him, but still he prayed.

"Lord Jesus Christ son of God, have mercy on me."

When the sun rose in the morning, Antony did too.

His body was shattered, but with some strength not his own, he pressed the heavy door open. The demons scattered in the sunlight, defeated. And Antony emerged, remade.

Antony would go on to become the most famous of the desert fathers, the unofficial forerunner of the monastic way in the desert. An Egyptian born into a wealthy family, he forsook the comforts of civilization shortly after stepping into adulthood, and wandered into the wilderness to pursue a life alone with God. His legendary life was read across Europe in the hagiographic “The Life of Antony,” written by Athanasius, the revered 4th century bishop of Alexandria.

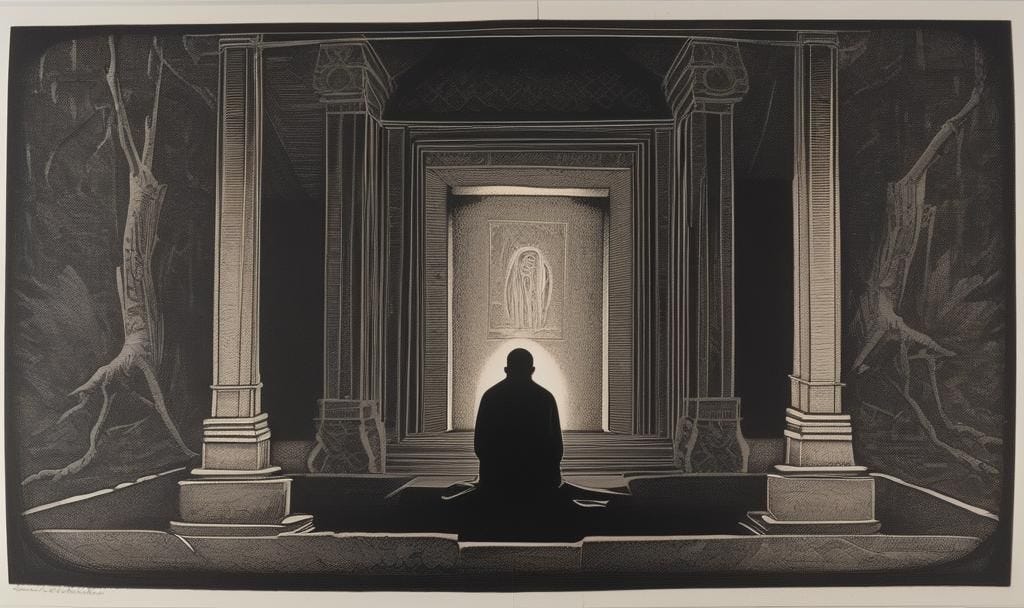

Antony’s self-imposed trial in that dark tomb took place in the early years of his devotion, before his departure to the desert. It was a rite of passage, a crossing over, into his new life. It was also training for what he would face in the wilderness—for the same place where he went to find God was also teeming with demons.

To the desert monks, solitude was an essential ingredient to holiness. They saw the distractions and temptations of the world as obstacles to real union with God. So they left the cities and villages of the Roman Empire to be alone with God in the deserts of Egypt, Syria and Palestine.

But the solitude they sought was not a tranquil refuge away from bustling society. Quite the opposite—it was a battleground. In the bleak quiet of the desert, they found demons in great numbers, out in the open, unadulterated by the superficialities of civilization. But this was not an unlucky discovery, it was the reason they went.

The first Christians throughout the Roman Empire saw suffering as a holy thing, and they revered martyrdom as a glorious privilege. Ignatius, the second successor to Peter as the head of the church in Antioch, was sentenced by Roman authorities to be devoured by wild beasts in the arena less than a lifetime after Jesus walked the streets of Jerusalem. During the long march to his death, he penned many letters to his followers, imploring them not to intervene to save him. A glorious end for the cause of Christ was the highest honor, one he was grimly grateful to receive. Ignatius’ faith and courage became an example to a long line of Christian martyrs that followed over the ensuing centuries.

But in the early years of the 4th century, the winds began to change. After the rise of the emperor Constantine, persecution of Christians began to quickly fizzle out, and new protections for Christians were issued across the Empire. The long nightmare of their oppression was ending. But with it ended the opportunity to suffer for Christ that they had so revered. So the desert fathers set out to find a new kind of martyrdom in the wilderness. If the beasts of the arena or the blades of state executioners were no longer their peril, then the demons in the desert were a worthy substitute.

Whether the demons they contended with were embodied enemies, or spectral emissaries of evil, or mythic symbols of a monk’s own inward temptations, they were certainly real. The tradition of the desert fathers tells us that their conception of “demons” was intertwined with the idea of destructive thoughts. They learned that to be alone, away from the world, was to invite the violent, unfiltered scrutiny of one's darkest thoughts to the surface. This naked struggle against the inner world of the mind and soul was their refinery of purification.

They took their cues from the long heritage of Biblical figures who found both great suffering and great revelation in wild solitude. Elijah, who grappled with suicidal depression, and heard the healing whisper of God on the side of the mountain. Jacob, who wrestled with God and came away from the riverside with both a wound and a blessing. Jesus, who resisted Satan’s advances in the lonely place, then was finally ready to begin his ministry.

Antony spent the majority of his life as a hermit in a desert keep, dueling with temptations, warding off demon incursions, and pressing with all his heart and soul into the presence of God. In that wilderness, in the crucible of solitude, he was forged into a titan of wisdom and holiness. Despite his isolation, his reputation spread like wildfire, and people around the Empire, from eager young monks, to church patriarchs, to emperors, sought his counsel. And his example comes down to us as an invitation, and as a warning.

Solitude, the desert fathers knew intimately, is not just a place of peace. It is the stage on which the ultimate battle of the self takes place. Where sin is surgically, or savagely, pried away from the soul. Where false selves are sentenced to die, though they never go quietly. Where lurking demons make their last fitful stand. And, finally, where God reforms and rehabilitates our very identity. Solitude can be a place of great struggle, and it can be a place of great grace, if we dare brave it.

P.S.

War of Silences is a poem I wrote to capture the carnage and the beauty of solitude. It was recently published in the journal “The Peace of Wild Things.”

You can read that poem and explore the journal here:

P.P.S.

This is the second in a mini-series on the spiritual discipline of SOLITUDE. You can read the first post here:

6 Phases of Solitude

In my essay earlier this Fall, "The Profane Presence of God," I wrote a line that I was nervous to publish because of how it might offend Christians. I published it anyway:

Stay tuned for more next week!

Thank you for reading!

If this post spoke to you or challenged you, send it to a friend or share it on social media:

To receive more posts like these and join the community, subscribe now:

Much love,

gb